Here’s an outtake from the book, an interview I conducted with Adrian Turner back in 2011 (I think) about not only the history of the Tri-Sonic pickup but also those that are in the Red Special.

The interview was conducted by email, so any typos or other grammatical inaccuracies are mine – Simon Bradley 2019

The origins of the Tri-Sonic pickup are firmly rooted in earlier European pickup manufacture. Coil type and base-plate assemblies are typical of the central European manufacturers (such as Fuma in Germany). These types of pickups were popular in the UK throughout the 1950’s under various brand names. Primarily designed for fitting to cello guitars, they were mostly fairly low output affairs, not ideally suited to solid body instruments.

Jim Burns had been using similarly constructed pickups, reproduced in the UK and adapted with different top covers, on a handful of solid body instruments manufactured in the mid to late 1950’s.

In 1959, Burns teamed up with Henry Weill and produced a small range of solid body ‘Burns Weill’ instruments, with complete electrical assemblies supplied and manufactured by Weill. These units were noticeably hotter, with visual influences similar to early Guyatone manufactured solid guitars, starting to appear in the UK in the late 50s.

As 1960 approached, Burns was keen to follow his own solo path and the Burns Weill partnership ended.

Burns new range of guitar designs to meet the new decade, were relatively thin, small bodied instruments (probably governed by the availability and size of quality timber, at this frugal time). Scaling down the size of the pickups made them more visually correct, whilst also allowing space for his innovative and rather complex (often confusing) control options. There was an awful lot going on inside early Burns instruments.

Burns’s pickups had stayed faithful to a proven formula but now appeared with flattened chrome covers with large holes punched into the top face (originally to allow for exposed magnets). Output of the units was extremely high for this period.

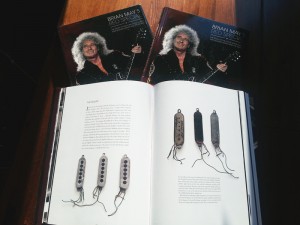

The Tri-Sonic made its first outing in two different versions and sizes. The upmarket ‘Artist’ and ‘Vibra-Artist’ guitars originally featured three separate small casing type Tri-Sonic’s with staggered, exposed Alnico pot magnets.

The more affordable ‘Sonic’ guitar featured a pair of slightly larger Tri-sonic’s, visually the same, but lacking the exposed magnets. Originally a single Alnico bar magnet was placed internally with a gloss plastic insert sandwiched beneath the covers, visible through the holes. It would be this larger cased variant which would remain in production throughout the decade and was the type purchased and fitted to the Red Special.

This larger version was more economical to manufacture for a few reasons. It used a slightly heavier gauge magnet wire, which made it far easier and quicker to assemble – and far less susceptible to manufacturing error/breakage (although this led to a bulkier coil, hence the slightly larger size of the units). The use of a single non- exposed bar magnet also saved both time and cost, when compared to fitting the individual exposed magnets, which needed riveting individually to the metal base-plates.

After the first few months of production, the larger pickups lost the Alnico bars which were replaced by two Ceramic block magnets, butted together to form a solid ‘bar’ along the length of the pickup. These Ceramic magnets are the type found in the Red Special’s pickups.

As various different Burns Guitar models appeared throughout the 1960’s, many were fitted with different adaptations of the Tri-Sonic, voiced to suit each instrument respectively (all marked with the standard Tri-Sonic logo). Magnet types were extremely varied (Alnico 2 bar, Alnico 2 pot, Alnico V pot, Alnico 3 Block (rare), Ceramic block and Ceramic pot magnets).

Each different magnet type and coil assembly producing tonal and output variations. A common mistake often made, is the belief that every Tri-Sonic manufactured in the 1960s will produce an accurate Red Special sound. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

In 1965 Burns and his then partners sold the company to Baldwin.

Around this time a degree of rationalisation seems to have occurred in pickup production.

Throughout the 1960’s Burns had not only produced Tri-Sonics, but also several other types of innovative pickups. Many of these units shared similar magnet assemblies and coils in varying different sizes. It is unknown if an attempt to ‘use up’ all existing stock ensued – or if a policy of ‘one size fits all’ was adopted, but for a while much bulkier coil assemblies appeared, rather uncomfortably ‘squeezed’ into Tri-sonic cases.

Although, both physically and visually larger, this does not mean that they are over-wound or hotter. It simply means that they were manufactured using a different size former and the thickness of the protective insulation was greater. It is these large type ‘rationalisation’ coils, which are present in the Red Special’s pickups.

Most regular Tri-Sonics from the mid 60’s period tend to average between 6.5 Kohms and 7.5 Kohms. The Red Specials pickups are no exception, with the centrally located pickup being the slightly hotter of the three.

Production of the tape-wound coil assemblies supplied to Burns, had always varied considerably. Examining a selection from each year, clearly indicates that coils were obtained from various sources. This is evident in the different materials, construction techniques and grades of magnet wire and hookup wires. Very early Tri-Sonic’s are often internally identical to Henry Weill’s units. Much later coils are akin to the Italian EKO manufactured items. Doubtless, there were numerous other armature suppliers too.

Like many products which are produced in relatively large quantities – they can often be haunted by undesirable quirks – especially if pushed beyond the use they were originally intended for. Such issues have been addressed on the Red Special.

The plated pickup covers were originally designed to be held in place by the spring action of the steel base-plates alone. This was originally aided during assembly by the application of liberal amounts of rubber cement. This not only helped to ‘glue’ the casings together, but also had an insulating affect and soaked up any internal movement or vibration. In later production, this was changed to a black bitumen based product – for the same purpose.

Over a number of years, this adhesive tends to completely dry out, leaving behind either a mustard coloured dust residue or a black powder coat type effect, visible on the inside of 60s pickups. Not only can this cause the covers to randomly spring off (just what you need midway through a performance) but can also cause severe feedback and uncontrollable whistling at volume. Quite why Burns never originally soldered the casings together (like modern units) is a bit of a mystery.

Tri-Sonics have always been expensive units to manufacture and it is unknown if this was purely down to cost or simply the faith they had in the adhesives at that time but production remained the same throughout the 1960’s.

The neck and bridge pickups of the Red Special have the internal voids filled with Araldite Epoxy, before being squeezed back together.

Modifications have also been made to the base-plate and fixing/adjustment tabs of the Red Special’s neck pickup, lowering the overall Inductance of the unit. This has a ‘fine tuning’ effect, to achieve a more focused tone from the neck pickup, relative to its placement on the guitar. The original black plastic inserts have at some time been replaced by extremely thin pieces of a textured black rubber material, visible through the holes in the top covers. Each pickup is shimmed for height and screwed down directly into the body wood.

In use, Tri-Sonics from this time period are renowned for their powerful, compressed tone when pushing an amplifier into saturation.

Because of their ‘full metal Jacket’ design, they can always be prone to a little natural high-gain feedback, but a skilled player can control and use this to great effect, producing lush harmonic overtones and seemingly endless sustain.

All Tri-Sonics by design, sense a wide string area, which favours midrange rather than over emphasising lows and highs. These units become extremely effective at volume when switched together in series, producing an extremely smooth ‘wall’ of compressed midrange.